On the map of Manhattan, almost every street breathes last names. They are on buildings, domes, columns, and even in elevator niches. Someone named a structure this way to emphasize its status. Someone else – to honor a relative or political leader. And sometimes the name simply stuck so much that it became a brand. These buildings can hide an entire era or simply hint: “This man had money and taste.” As always in the big city, the thin line between recognition and ambition… made of concrete and granite runs between them. Let’s try to feel it out together – on manhattan-future.com.

Why Architecture Adopts Names: A Bit About Memory and Ambition

Imagine a typical Manhattan street – facades rise like memorials, the names on them are like inscriptions on gravestones or plaques. In this city, a building easily transforms into a stage for memory – something more emerges from the four walls: a symbol that carries a foreign name. Sometimes this name belongs to a developer in a hat, sometimes to a figure who left a mark on the city. And yes, sometimes it is also marketing, because the name brings interest, status, and adds recognition.

On the other hand, there is a hidden task: a name on the facade obligates. It places the building under a certain scrutiny – will it meet expectations? Will it become just a monument to the owner or a true monument to significance? Architecture becomes a territory for discussion – about memory, about legacy, about who has the right to be immortalized.

And here the question arises: who decides who gets the plaque on the facade? In such a vast district as Manhattan, this question is particularly palpable: the boundary between honoring and vanity is often so subtle that it is barely visible between the columns. But when someone’s name appears on the facade, it is already a piece of the person in concrete.

Manhattan Speaks in Names: Memorial Buildings with Human Stories

Buildings with names are almost a separate genre in Manhattan’s urban landscape. They form that layer of memory that will not be erased by new development or a sign change. In this section – several examples of architecture that has become a memorial in the literal sense of the word: with a name, history, and character.

Low Memorial Library

In the center of the Columbia University campus stands a monumental structure with a dome and stairs, which students have favored for sunny breaks and loud protests. This is the library named after Abiel Abbot Low – the father of the university’s then-president, Seth Low. Seth himself funded the project at the end of the 19th century. The domed form and classical columns create the impression that this is not just an academic building, but a temple of knowledge and family memory.

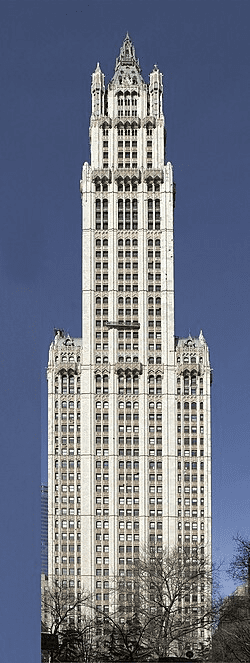

Woolworth Building

This Neo-Gothic beauty is often called the cathedral of commerce. Frank W. Woolworth, the department store magnate, commissioned the construction and paid for it in cash – $13.5 million. At the time, that was a staggering amount of money. Until 1929, the Woolworth Building remained the tallest skyscraper in the world. And also – a monument to how small trade can grow into a true architectural cult.

The Ansonia

On Broadway, closer to the Upper West Side, stands a building with domes, balconies, and an almost Parisian chic. It was once a hotel, now it is a residential building. The name – The Ansonia – comes from Anson Greene Phelps, the developer’s grandfather. This is an example of that form of memorialization where a relative’s name becomes the sign of an entire architectural project. The decor is Baroque, with notes of eclecticism, as if hinting: here, memory is not shy of splendor.

Rockefeller Center

This ensemble of 19 buildings between 48th and 51st Streets is a city within a city. It was founded by John D. Rockefeller Jr., and since then, the Rockefeller name has been ingrained in the cultural map of New York. As RockefellerCenter.com notes, it was the largest private construction project of its time. And it remains a symbol of how private initiative shapes public territory.

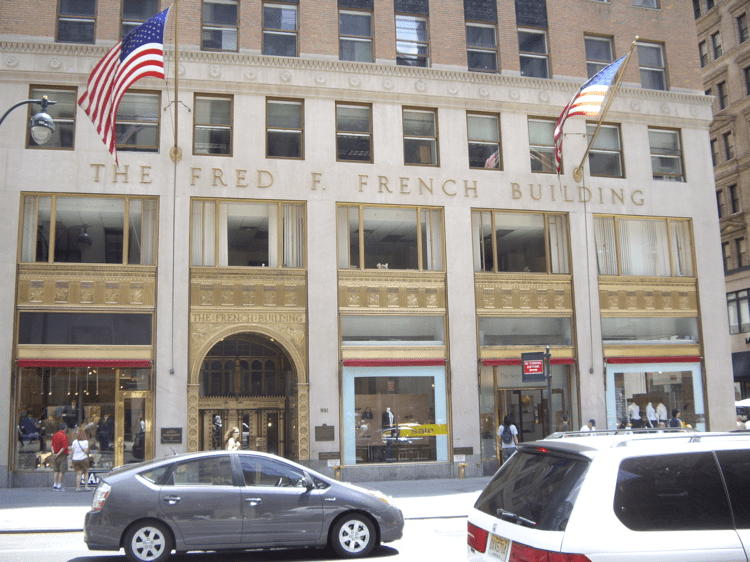

Fred F. French Building

This skyscraper, which bears the name of the developer – Fred F. French, carries his style in every ornament. The building stands out with Art Deco facades featuring Mesopotamian motifs. This was one of the first attempts to integrate the idea of “a living environment for the middle class” into the development. The name on the building here is part of the architectural philosophy.

Fuller Building

George Fuller’s company was initially housed in the Flatiron Building, but later built a new (taller) building on Madison Avenue, also named the Fuller Building. Now it is this one that bears the name of the developer.

The Fuller Building’s facade is somewhat strict and restrained, as if construction ethics itself had turned into architecture. There is no superfluous glitter here – only lines, stone, and the ambition of an era when the skyscraper was still a sensation. And inside, there are galleries, antique interiors, and echoes of that New York elite who knew how to engrave a name in marble.

David Dinkins Administrative Building

This was previously the Manhattan Municipal Building. In 2015, it was renamed in honor of David Dinkins – New York’s first Black mayor. This decision carried, among other things, political weight: the name on the facade became a reminder of the struggle for equality in the heart of the city. The architecture here is classic, with a dome and colonnade, but the meaning is very modern.

The Name on the Facade – Is It Marketing or Legacy?

When someone names a building after themselves, it might look like a desire to leave a mark. But between a humble “in memory of” and a loud “I’m the boss here” – there is a huge difference. Manhattan knows both options.

There are cases when the name is part of the brand. For example, the Woolworth Building is automatically associated with the era of American retail growth. This office building is the architectural showcase of an empire. An entire family literally wrote itself into history through architecture. The scale of the project was such that private initiative turned into a national-scale platform.

At the same time, the name can impose responsibility. A building with a last name on the facade becomes part of the reputation – both of the one who built it and the one who uses it. If the reputation cracks over the years, like plaster, then a discussion arises: should the plaque remain? This has often become a topic in the US – particularly in universities, where buildings named after slave owners or sponsors with questionable biographies became a stumbling block.

This dichotomy – between brand and legacy – is clearly visible in newer memorial architecture. On the one hand, the name adds weight. On the other – it turns the façade into a mirror of the era. Sometimes – with a not very pleasant reflection.

Where Is Memorial Architecture Heading?

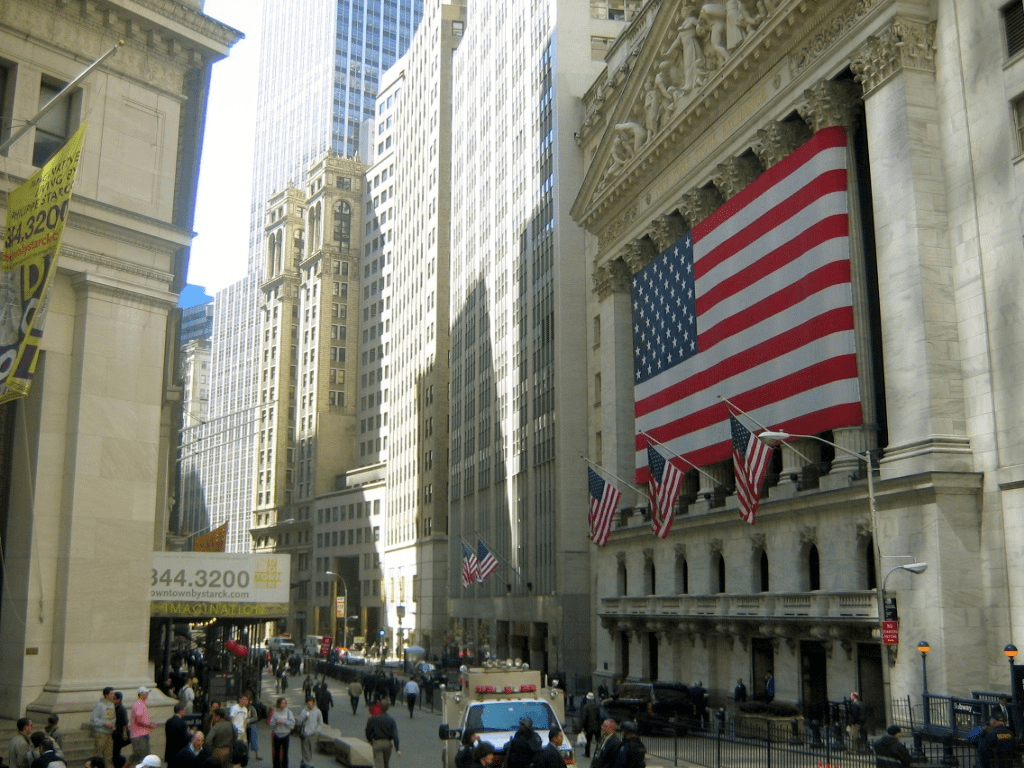

Currently, the plaques read Woolworth, Low, Rockefeller. But who will be next tomorrow? In the 21st century, the architecture of memory is also undergoing changes. New values – equality, representation, historical sensitivity – demand a review of who and why we honor. What is there to say when even Wall Street is changing its appearance and reputation (once commercial, now forming its image).

One example is the renaming of the Manhattan Municipal Building in honor of David Dinkins. This is a signal: today, recognition is given to those whose presence in stone was long impossible. Architecture, which for decades “spoke” with the voices of white patrons, is now changing its tone.

Of course, memorial architecture is unlikely to disappear – it is too deeply rooted in the urban fabric. But its content and form are changing. Increasingly, instead of self-glorification, collective memory is found, instead of marble with a last name – artistic installations or interactive spaces that tell the stories of many. And perhaps it will be even more interesting later: buildings without names, but with histories that do not need to be carved, because they live in how we feel those buildings.